A little under three weeks ago, I started hormone replacement therapy. Once a day, every day, I swallow a tiny quarter-pill of Cyproterone and rub a little bit of estradiol goop on my thigh. These two innocuous rituals will, surreally, gradually shift my body’s hormonal balance from a male one to a female one. They’ll give me softer skin, weaker muscles, and breasts. My fat will start migrating down from my belly more towards my hips, and my erections will be softer and fewer. Instructions which have been dormant in my DNA my whole life – imagine dusty folders in the back of my body’s filing cabinet labelled activate in the event of estrogen – will start getting cracked open and followed by my body’s dutiful cells. And there’ll be a variety of mental and emotional changes, all of which seem highly personal and difficult to anticipate.

The obvious question is: why am I doing this?

The truth is I only kind of know. I’m not in the position of ‘always having known I was a girl’, or even of having a locked-in ambition to pass as a cis woman. When I’ve talked about the transition I’m undergoing, I’ve described it as ‘moving into a more transfeminine space’. Just making a daily, iterative decision to feminise my physical existence, and seeing where that goes. Once I’ve been on it for longer, I’ll probably be in a better position to say whether ‘trans woman’ is the inevitable destination here, or whether I’ll keep finding something important in a looser, fuzzier, and more nonbinary kind of transfemininity.

Either way: there are plenty of read-as-masculine signifiers that HRT doesn’t change, and even years down the line, passing as a cis woman may honestly just take more effort than I’m willing to put in. (Whatever kind of transfemme I turn out to be, I genuinely think it’s important that I get to be a bit lazy about it.) So I’m not really imagining myself as passing or glamorous or anything; I’m just imagining myself happy. I’m imagining myself as a kinda goofy transfeminine person with a confusing palette of gender-signifiers, a warm vibe, and a bunch of board games. That feels like a harbour I can sail towards.

This is going to be a extremely long post (6000+ words lol), so it’s really only for the genuinely interested. The tl;dr ‘action items’ are basically:

- I’m going by Ada in most contexts now (not work or official stuff yet, but pretty much everywhere else)

- I’m using both she/her as well as they/them pronouns

- ‘nonbinary transfemme’ is probably my favourite nomenclature for myself at the moment.

But for anyone who’s interested in an extravagant amount of detail about how I’ve come to this point:

Part 1: One Must First Become Aware Of The Body

Going back now to read the post where I originally named being nonbinary and agender is an interesting exercise for me. Some parts induce a tragicomic wince – like, imagine making a big deal out of identifying with a J.K. Rowling character in the post where you’re coming out as trans, lmao shoot me – but I mostly stand by it! It was how I understood myself at the time, and within the pragmatist framework it lays out – aspiring towards gender as a self-negotiated tool for pleasure and meaning, as opposed to a site of coercion and limitation, and labels as only being good insofar as they’re useful – were all the foundation I needed to have eventually arrived at the place that I have.

One omission in that piece that’s fairly glaring in retrospect, though: I don’t really talk about my body at all. I briefly mention that I felt disassociated from it growing up, and I later make the polite reassurance that ‘I’m not looking to alter my body in any way’. But those are the only lines my body gets in the whole production! The rest of it takes place in the realm where I’m obviously more comfortable: in words and ideas. Part of this is just a reflection of the cerebral, head-in-the-clouds kind of person that I am, but another part is rooted in the specific philosophical framework that enabled me to come out as nonbinary in the first place: Rortyan pragmatism.

I’ve written about the way pragmatist philosophy enables us to conceive of gender before, but without getting too in the weeds: Richard Rorty is an important guy for me. I felt pretty indifferent towards a lot of the philosophy I studied in my bachelors degree, but when I finally encountered Rorty in my third year, it felt like being given a fresh oxygen tank on a long underwater trudge. Finally, someone asking all the same questions I was! He had this marvelous way of seeing all the different ways you could conceive of the world as different ‘vocabularies’, which he had the gift of being able to take on and off as smoothly as hats. In Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity in particular, he gave me a vocabulary of his own to describe the internal project of self-creation: the way in which an individual can, without imperialistically assuming that it must be the same for everyone, “work out their private salvation, create their private self-images, reweave their webs of belief and desire in the light of whatever new people and books they happen to encounter.” There’s this sense, reading Rorty, of the self as a fundamentally poetic project – responding to the destabilising chaos of a godless universe not with terror or ennui, but with the gusto of an artist – and as a 22-year-old, it absolutely sang to me.

But Rorty also placed certain limits on how far you ought to take these private projects of self-creation. He was extremely committed to liberal democracy, and made a strong distinction between public and private. In private, Rorty says, you should feel free indulge in whatever poetic fancy of self-creation you like – there, you make the rules – but in public, you still need a common civic language. You need to be able to be intelligible to your fellow citizens, and to be able to communicate with them for collective ends. This was essentially Rorty’s way of reconciling all the postmodern wibbly-wobbly truth-shattering with the liberal democratic societies that he was so fond of (and which had, after all, produced the postmodernists, who he was also very fond of).

At the time of writing my nonbinary post in early 2015, I would have happily told you about how my understanding of my own nonbinary identify was influenced by Rorty’s poetic approach to self-understanding. In retrospect, though, I can see that I was also really influenced by his notion of the public/private split. That original post is suffused with the idea that ‘this is how I’ve come to understand myself – I think it’s neat – but don’t worry; I promise I’m not going to make anyone else do anything about it.’ I instinctively shied away from the idea of making my gender stuff anyone else’s problem. As much as I didn’t enjoy having a male body, the idea of transitioning to the point where a cashier or a stranger on the street might be confused by me – i.e. making myself less intelligible to my fellow citizens – felt like an imposition on others that I couldn’t face making. I couldn’t countenance the idea of modifying my body, because in some sense that would be making public an aspect of my self-creation that Rorty had coaxed me into thinking of as fundamentally private.

To be clear, I’m not dragging Rorty here. Being the person I was, I think I needed that purely private space of self-creation before I could be capable of making any of it public. And even as the public/private split gave me some particular anxieties, it also valuably alleviated some. I’ve spoken to so many baby transes who’ve been panicked about making sure they’re labelling their gender “correctly”, that they’re using the right language and slotting everything into its ultimate place in the true taxonomy of reality, and the biggest relief I can give them is simply permission to stop worrying about the goddamn metaphysics. With Rorty’s framing of the question of self, you can just stop asking gender’s unanswerable questions, and start asking more grounded and productive ones. Not “what am I?”, but “what would I like to be?” Not “is this label correct?”, but “what does this label do for me?” What possibilities does it open up? What might it foreclose? How do you feel about what you could make of yourself with it?

It’s pure pragmatism! It’s focusing on the language here as a customisable set of tools whose value lies in what they allow us to do. It’s a turn away from metaphysics and towards self-understanding as a practical private poesis. (I usually don’t say that to the baby transes in quite those words, but the point gets across.) I continue to think Rorty’s pragmatism is a pretty brilliant frame to have in beginning to think through your gender; it gets you asking the more helpful questions.

At the same time, though: my starting on hormones is clearly a step away from Rorty’s public-private split. HRT is a process that will (slowly, eventually) inscribe this aspect of my private poeisis onto my visible body – the body I take into the public square – and I’ve had to become comfortable with that. Rorty died in 2007, so I never got the chance to take his temperature on the subject, but I have to think he’d at least be interested in nonbinary identities, in the same wry way he was interested in all eccentric projects of self-creation. But by the same token, I suspect he’d be a bit more purse-lipped about the idea of someone like me going on hormones. Somebody who needed them to relieve otherwise-crushing dysphoria, I imagine he’d be okay with, but a more marginal case like me? That feels less certain.

If I were to argue my case on a purely philosophical level, I’d probably try to interrogate how the ‘civic democratic language’ is constructed. Like, sure, after being on hormones long enough and carrying around a bunch of mixed gender signifiers, I may confuse some people in public. But I’m a citizen too, and is it really a shared democratic language if it isn’t created democratically? It seems like a mistake to overstate the value of the false intelligibility gained by me going out into the world in man-drag, when what I’m offering instead is an opportunity to rework our social scheme of gender intelligibility that demonstrably isn’t serving the populace particularly well. Plus – on a more specific and groundedly ethical note – it’s increasingly true that most people don’t actually want to misgender others, so hiding my gender in public may not actually be the obvious ‘thoughtful’ move it once seemed.

Really, though, my way through this problem hasn’t been philosophical at all. It’s just been a steeling of nerves. It’s been facing my body, getting more and more certain that I want to act and be related to from a more feminine position than my body predisposes, and realising that I can actually change that. But because of how useful Rorty’s framework was in allowing me to articulate my gender stuff to myself in the first place, convincing myself that it’s okay to expand that desire out from my most private and intimate relationships – and more into the public sphere – has genuinely been the hardest aspect of all of this.

Something that helps, ironically, is when misogynist pseudo-intellectual twerps like Jordan Peterson complain about the social unintelligibility of nonbinary people. When I’m worried about it for myself, my anxiety can lend it the heft of a real imposition, and it can produce real fear about taking up unmerited space in other people’s apprehension. But when it’s a dickhead like Peterson voicing it from the outside, it becomes massively easier to just be like “Oh, go fuck yourself! You can be confused if you want to be, but it’s really not that hard! If you just treat people with baseline human respect you’ll actually be FINE!”

Distastefully, up to this point in my life, if I’d ever had the misfortune of meeting Jordan Peterson, he’d “know how to treat me”. Perhaps he’d smell something queer on me – and his hackles would certainly be raised as soon as I said anything – but I would be more or less socially intelligible to him as a man. But honestly, he should be more confused than that by me. I’m a different kind of queer than he’d likely assume, and there’s obvious negative utility to the scheme of gender intelligibility as he practices it. Given that his response to nonbinary people is not actually merely confusion, but active hostility for daring to make him confused, it makes my response pleasantly straightforward.

“Sounds like a you problem, my guy!”

Part 2: The L word, or, the breeze in the valley

Okay, now I have to put my money where my mouth is. I made a big deal in Part 1 about having grown more confident in letting these private gender-things be more public, but this is the part I’m by far the most nervous about talking about. Did I keep putting off this section and have to circle back to it after I’d written everything else? Did I put a bunch of philosophy before this so that fewer people would see it? Who can say.

Because the truth is, in this gradual shift from ‘agender nonbinary’ to a clearer sense of my transfemininity, the formative word – the guiding lantern steering me to where I want to go – hasn’t been ‘woman’. The formative word has been lesbian.

I’m just such a fucking lesbian already! Every relationship I’ve ever had has either had lesbian vibes and worked, or tried to be a straight one and failed miserably. Queer people usually understand this a million times better than straight people: sexuality isn’t just about who you’re attracted to; it’s also how you want to be found attractive. And when women find me attractive as a guy, I shrivel up like a time-lapsed leaf. Sex doesn’t work; I’ll dissociate and clear right out of my body within 30 seconds of genitals becoming involved. Even being flirted with by someone who’s clearly experiencing me as a guy feels rotten, like I’m fraudulently advertising something that the store simply does not stock.

But every time there’s ever been a flash of a woman or transfemme finding me attractive in a gay way … Christ, that’s a whole different thing. It feels impossibly good, ‘getting away with something’ good, good in a way that I’m not sure I’ll ever entirely feel that I’ve earned. I honestly never dared to think of myself as a lesbian before other people – romantic partners in quiet moments – started naming it as something that felt obvious to them. In the less-lit corners of an intimacy, you can build a lot of curious shapes without necessarily having to name them. It was only when these partners started naming these shapes I kept building that I was able to see, briefly, light breaking through fog, a glimpse of what they saw.

And look, I know that there are going to be cis lesbians for whom this is contentious. I’m sure I’d get into less trouble if I confined myself to the roomy expansiveness of queer (with its “principled and deliberate fuzziness”, to borrow a phrase of Rorty’s I always loved). But – I don’t know what to tell you! Lesbian just captures something vital about the way I love and want to be loved. Look how clearly the pull of it was present in the 2015 nonbinary post:

Another thing I can understand a lot better in the light of this realisation is how much, ever since I was young, I’ve loved and identified with gay women. I don’t mean ‘gay women’ in the sense of some big homogenised group; I mean specific gay women, who made me feel things that no-one else in my life did. God, I’ve had so many crushes on queer girls. I used to have a whole stand-up bit making fun of myself for it. Over and over, I kept having these strong feelings for musicians and actresses and characters who I would only discover later weren’t straight. I kept feeling weird about penis-in-vagina sex, and secretly preferring all the other kinds. I kept surreptitiously reading Autostraddle.com (”they have great taste in books!”, I’d say to the imaginary inquisition in my head). I kept having these experiences of feeling deeply at home amongst gay women, but only being able to talk about them in really cryptic ways (look at this post from 2010, at the way I grammatically absorbed myself into “the crowd”). I kept crying reading Adrienne Rich. This is … whatever it is, it’s a thing.

And it makes sense, right? If I’m not actually a man but I am attracted to women, of course I’m going to feel more drawn to queer women than straight women. Of course I’m going to feel more of an affinity for queer and lesbian relationships than heterosexual man-woman ones. They’re closer to something I could actually feel fully seen and affirmed in. They’re closer to the kind of people who could find me attractive, not for the man I’m supposed to be, but for who I actually am.

They’re closer to who and where and how I actually want to be.

“Whatever it is, it’s a thing.” I was terrified to publish that back in 2015, because I was (and still am) low-key terrified of ever being thought of as intruding on lesbian territory – but it was all just getting harder and harder to ignore. An interesting wrinkle that’s developed in the intervening years: in the original post, I listed a bunch of examples of “musicians and actresses and characters” who I had unaccountable strong feelings about, all of whom identified at the time as lesbians, but two of whom have since come out as transmasc. (I have more than one ex-partner who has too.) There’s a whole fuzzy topography of feeling here, where sometimes what I can pick up on in people is a kinship in the way we’re awkwardly working around our own gender, and an unshakeable sense that this is a person who could see me. I’m making a big deal out of the word ‘lesbian’ here, but I don’t mean it particularly restrictively. This is what I wrote about my gender in that 2015 post:

When I look into the deepest parts of myself, outside of how I’m treated and read and understood by others, I don’t feel any gender at all. I just feel a still, calm, responsive space.

An open enclosure; a gentle valley.

A response waiting to make itself.

And a particular kind of yearning to make it.

[…]

If the core of me is this adaptive, bendy, pragmatic neutrality, the main thing I have available to listen to is the quiet voice (the breeze in the valley) telling me who I want to adapt to. And that breeze has only ever blown in one direction.

I was being coy and poetic about it in 2015, but “who I want to adapt to” is queers and trans people, and always has been. The breeze in the valley is lesbianism. I know that might sound like a strange, thin, rebounded way of identifying my desires here, but it’s the direction I’ve been travelling in since I first learned to walk, and the light by which my relationships make by far the most sense. My last partner, especially, was remarkable for the unshakeable and clear-eyed solidity with which she experienced me as a lesbian – even before I’d actually fully articulated it to her – and that was huge. It made it so clear not only that it was right, but also that it was simple.

Like, realising in my 20s that I kept getting crushes on lesbians was one thing. (That can, with the right spin, merely be quirky.) But realising that nothing makes me feel more whole and seen and myself than being loved as a lesbian?

Well, shit. That’s a whole different thing. And it puts me in a much more vulnerable spot.

Part 3: :3

Some years ago I saw (or possibly hallucinated) a tweet that’s stuck in my mind ever since. I haven’t been able to find it again, but that’s probably unsurprising, as it’s the exact kind of thing a person might tweet high on weed gummies and then delete 12 hours later. It was from a trans woman, accompanying a photo of her estradiol and spironolactone pills, and to the best of my recollection, it read as follows:

“just taking my little faggot pills :3”

Now, look, I’m a cautious kind of person. With the reclamation status of the word ‘faggot’ still so niche and contested, I probably wouldn’t personally throw around the word so cavalierly. It’s honestly impressive how many different political traditions would be entirely aghast at that tweet, for a whole variety of different reasons. But at the same time:

What a sentence, right?

To my mind, the tweet has power because it’s a silly and ribald articulation of a genuinely powerful truth. By taking HRT, you’re making the deliberate choice to make your body, your sexuality, and your existence more deviant and confusing from the perspective of heteronormative society. It’s deviant behaviour, yes, but it’s also inscribing that deviancy in your body’s material composition. You’re choosing to actively increase the likelihood that somebody will, at some point, in anger and as a way to punish and demean you, call you a faggot. They are, in this extremely literal social sense, little faggot pills.

(Obviously there are straight trans people, but I think the point still holds. Even the trans people most committed to staunchly performing straightness and being “one of the good ones” – your Blaires White, et al – are still extremely liable to have ‘faggot’ lobbed at them at any moment, even by their fans. It’s not a word with a particularly precise definition; it’s just a hammer.)

But when queer people pick up the hammer ourselves – perhaps do a gay little dance with it – that can lend real courage. I haven’t liked to talk about this much, but years ago, I got a death threat on the street for wearing a skirt. I was waiting for a tram less than 100 metres away from where I was living in Brunswick (Brunswick! Lefty progressive Brunswick!), largely presenting as male except for a lovely fuchsia wool skirt. A gaunt, balding, middle-aged man walked up close to me and whispered in my ear, “If I had a gun, I’d shoot you in the head.” I wish he’d shouted it.

At the time, I convinced myself that I was okay, more or less. It was clearly an empty threat, and I obviously knew I signed up for the possibility of this when I started dressing in more gender-variant ways outside the house, right? But the truth is: I pretty much stopped wearing skirts outside after that. Not straight away, but after my resolve had slowly but steadily drained out of that puncture-point. It became a calculus of “is it worth the hassle” and “ugh, I just really don’t want to be so visible today”, which more and more frequently led me down the path of least resistance.

Which means that the abuse worked. Even though I could tell the story in a way that made me sound cavalier about it, I let myself be cowed. One of the really significant things about HRT is that, in a certain way, hormones are like a skirt you can’t take off. Obviously there are always presentational decisions you can make on the basis of safety, but once you’ve been on hormones long enough and your body has really changed, it can become tough to fully boymode. Even if you’re not passing as a cis woman, your gender weirdness is written on your body, in a way that would probably anger my gaunt Brunswick murder-wisher just as much – and for exactly the same reasons – as the sight of ‘a guy in a skirt’ did.

This, I think, is why I’ve always been so captivated by the ‘faggot pills’ tweet. To have such a fun, silly, gleeful attitude towards becoming a faggot, towards the choice to actively make oneself more faggotlike (in the deeply real social sense of ‘liable to be punished as one’) – there’s a source of queer power in that which is basically thermonuclear. It could power all of the gay submarines. It could Superman-spin the world forwards. May we all live in its glow.

Part 4: Dysphoria, A Ghost Story

The history of the medical gatekeeping of trans people has mostly been a nightmare: a small cadre of creepy cis men holding all the levers of power and witholding healthcare to any trans person they didn’t find sufficiently fuckable, or sufficiently willing to parrot their own theories back to them. At most times and places when doctors have been in charge of deciding whether not a trans person should get access to hormones, I straight-up wouldn’t have qualified. The medical model of transness has always made suffering its yardstick, and I’ve just never had the kind of loud, acute, “unable to live as a boy” dysphoria that could have made me certain from a young age that I wanted to transition. It’s all been a lot foggier than that. And when the model is “HRT is medicine purely to alleviate the symptoms of gender dysphoria, which is one thing and defined by distress”, people like me aren’t gonna make the cut.

Here’s the problem, or one of them: the instruments needed to locate the gender dysphoria are pretty ruinously vulnerable to the exact forces they’re attempting to measure. If I’ve gone through life feeling disconnected from my body, that could potentially be a marker of dysphoria, but it also means that I don’t have any of those viscerally strong feelings people sometimes describe of having the wrong body. The disconnect is such that I’ve just never been able to access any strong feelings about my body at all. What exactly is one to do with that? It certainly doesn’t sound very sturdy on an intake form. To the extent that I have gender dysphoria, it seems that one of its primary effects has been to bury in sand my ability to access my own feelings about my gender and about my body.

Don’t get me wrong: it wouldn’t be hard to line up a bunch of facts about my prior history – for instance, the way I always took every opportunity to play girl characters in video games; the way I refused to even contemplate going to an all-boys school when that choice was offered to me; the wobbly little smile I’d get whenever anyone mistook me for a woman online or from behind; the way I once broke down sobbing at a stupid “what would you look like as the opposite gender” photo filter; the way I kept dissociating through straight sex – and say I dunno man that sounds pretty dysphoric. But there always seemed to me to be other potential explanations for them, which I’ve spent the last 20 years dutifully exploring and exhausting. And the truth is, at most gender clinics historically, none of that would be enough to get me a diagnosis.

Because – and I know this is in a very deep, unpleasant, grey way – I could pretend to be cis. if I couldn’t transition, I wouldn’t die. I’m a very accommodating person, with a bone-deep aversion to ‘making a fuss’. If transitioning weren’t an option for me, I’d just get on with things, live a cis life, and try to find as much happiness as I could in the seams. At most gender clinics historically, if I told them this, they’d immediately say, ‘Oh okay then! Well, no need to transition then. To be honest, we only begrudgingly allow it for the people who insist that they couldn’t stand living otherwise (and even them, we make insist it for years and years before we relent). But a cis life is plainly the superior outcome, so: do that. Feel free to take a lollipop on your way out.’

It’s only been in recent years that an informed consent model has started, quietly, in some places, to be put in place for adults seeking hormones. Informed consent is essentially where, when you come to an endocrinologist wanting to be put on gender-affirming hormones, they don’t see it as their job to assess whether you’re ‘really transgender’, but rather – assuming that you’ve thought about it, and it’s your decision to make – they see it as their job to make sure you know exactly what the hormones will do, exactly what the risks are, and how to take them safely. This is the model my GP and endrocrinologist have used with me, and I honestly can’t express how grateful I am for that.

In my first session with my endocrinologist, we had a 10-minute chat about what my deal was and why I wanted to try them (friendly and non-invasive, and I guess just checking for the most obvious of red flags), and then the rest of the hour was straightforwardly about the practicalities of what the hormones would do. It was perfect. If I had to go through the kind of interrogative, invasive assessments that are still common practice – which are better than they used to be but which still ask a ton of “are you really just a pervert” questions – I honestly don’t think I would have made it. I wouldn’t have wanted to lie. I wouldn’t have wanted to smooth out the bumps in my story to present a more standard narrative. I wouldn’t have been able to deal with the violations of privacy, the insinuations of ulterior motives, and the need to fit into a tiny diagnostic costume. Even if I’d had a relatively compassionate doctor simply following current WPATH standards, I strongly suspect that I’d be knocked back.

Which means, I guess, that I can’t feel too much chagrin about having ‘taken this long’ to start hormones. If I’d attempted it even 10 years ago, I probably wouldn’t have been able to. I wouldn’t have been able to find an endocrinologist willing to prescribe on an informed consent basis, I wouldn’t have had the stamina to endure all the invasive assessments, and I definitely wouldn’t have had the nerve to self-medicate. Informed consent was the only way I was ever going to be able to transition. Which, given how immediately and obviously the right decision I feel it to be, should probably give us pause about the whole medical model of transness.

Here’s something that I think is illustrative. Recently, some clueless cis person on Twitter posed this question:

The reaction from trans people I saw was pretty much universally negative. People compared the prospect to a lobotomy, to conversion therapy, to brainwashing, to being killed and replaced by someone different. Now, if you asked those same trans people whether they would accept becoming cis as their gender, I suspect you’d get much more mixed results (though still far from universally affirmative). But when it came to the prospect of simply ‘taking away their dysphoria’ – turning them into someone who was, in the language of those old awful clinics, ‘content with their birth sex’ – virtually every trans person replied with the horror and revulsion of someone facing the prospect of their personhood getting wiped from existence.

If HRT really was treatment for an ailment called gender dysphoria, you wouldn’t really expect that, right? Like, if you offered people with kidney stones a magical new treatment that could simply get rid of them painlessly, pretty much 100% of sufferers are saying yes, with no hesitation. Ailment after ailment, very few people are saying no to instant painless miracle cures. But transness is clearly different, right? Even though the medical authorities have always focused so exclusively on the pain of being trans as the problem in need of medical redress, that’s clearly not all that’s going on. Trans people don’t want the kind of ‘cure’ that tweet proposes, because transness is genuinely so much more than the pain caused by being it in a transphobic world. It’s a core ingredient in our stew, a central thread in our life’s narrative, a fundament of our self-concept. It’s inextricable from the people we are, to the extent that the ‘miracle cure’ proposed in that tweet could literally only function by destroying the person.

Now – before I get too over my skis – it’s obviously politically important to recognise trans HRT as healthcare. Hormones are a medically complicated dimension of the body, and I do think it’s generally a good idea to have a trans-competent endocrinologist involved (at least in the beginning) to do blood tests and explain the risks and be on the lookout for the kinds of medical complications we might miss. But at bottom, I feel like hormones are a question of bodily autonomy. We should simply get to do this with our bodies if we want to. We shouldn’t need a ‘diagnosis’, as though what we have is a disease in need of cis people’s cures; we should just be able to decide if we want to shift ourselves in this way.

Here’s the truth of it for me. When I think about my daily ritual of taking my Cyproterone and rubbing estradiol goop on my thigh, I don’t experience it as a medical treatment. I certainly don’t think of it as ‘medicine’ I’m taking for a disease I have called ‘gender dysphoria’. I think of it as a change I’m choosing to make to my body for my own reasons: more akin to the way that some people choose to tattoo themselves, or exercise in pursuit of a particular form. Those analogies might risk coming across as minimising, but I don’t mean them to be. Starting HRT feels like one of the most important decisions I’ve ever made – a fundamental reorientation of my relationship to myself and to how other people will relate to me – and even if the experiment ends up leading to me going back off them, it’ll still have lifelong repercussions. But while it’s clearly medical in the sense that it involves making some alterations to my body chemistry, it’s honestly difficult for me to conceptualise my own HRT as a treatment. Not in the way I’ve been treated for other health problems I’ve had. For me at least, it’s just a fundamentally different kind of project.

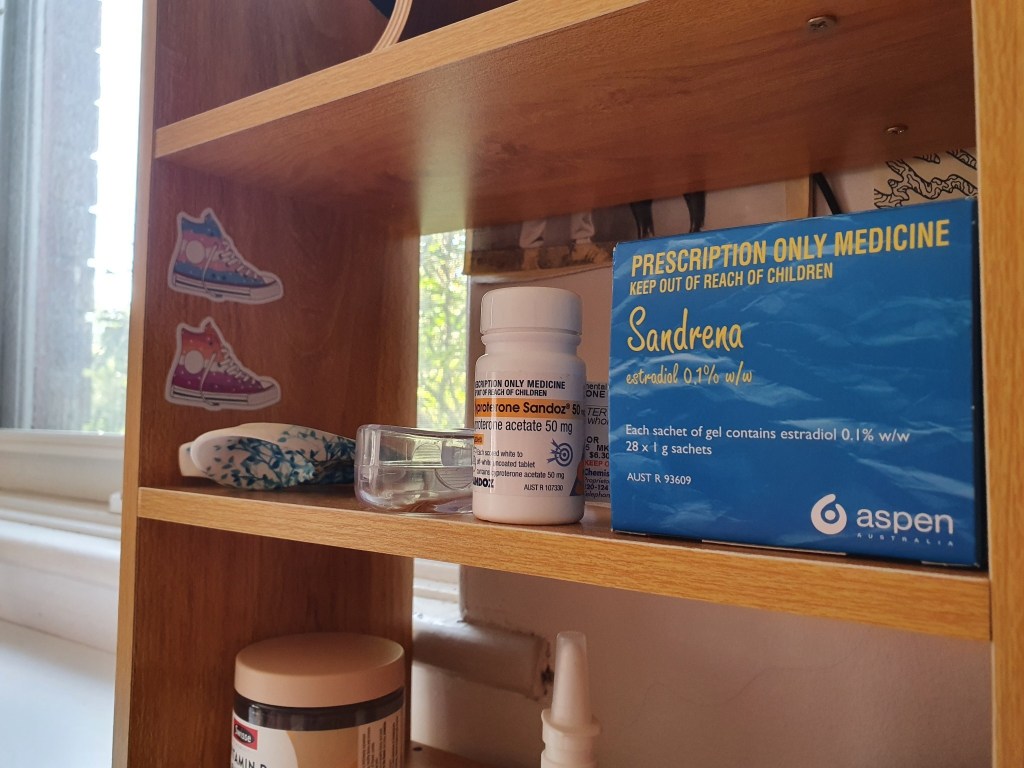

Whimsically, my organisational instincts were already gesturing at all this before I’d really articulated my thoughts on it. When I first got my hormones, I kept in the bathroom cabinet. Obvious place for them, right? But after a few days, I realised I had this nagging sense that this was the wrong spot for them. I’m very particular about the organisation of my belongings; I like to be able to see everything at once, and get a lot of satisfaction out of having everything well-categorised. And having my trans stuff in my medicine cabinet, I realised – alongside the cough medicine and diarrhea-relief capsules and antiseptic gargle – was rubbing dissonantly against that instinct. These things are in different categories. So I took the HRT stuff out of the medicine cabinet, and instead arranged in on a dedicated little shelf beside my bed. On it, in a neat little row, sit the pills, the gel, a little plastic pill-splitter, and a pair of scissors for opening the little sachets the goop comes in.

It was a great decision; my organisational instincts satisfied. Ever since, I’ve often found myself just looking fondly over at the shelf – all the tools laid out for my favourite daily ritual – and sharing a little smile with myself.

Part 5: The bottom line, the simple truth, the thigh in the ointment

All of what’s preceded this amounts to an explanation of why I started hormones, but it doesn’t secure any particular outcome. This is an experiment, and like any good scientist, one must be prepared to get all sorts of results. If I try them and they end up doing nothing for me, I am perfectly prepared to accept that. If I stay on them for years but eventually stop appreciating the changes and abandon the whole idea, I am steeled to accept the more permanent changes as dignified monuments to my willingness to answer a question that was worth asking. (“Why do I have these tits? For science, dear boy. For science.”)

But listen.

It’s early. It’s obviously stupidly early. But so far the experiment’s been going great.

I’ve been in a consistently ebullient mood: grinning at nothing, dancing in the shower. I’ve started exercising (which I’ve never done uncoerced before in my life), because it turns out that once I make a single real decision in relation to my body, I feel more invested in it, and find myself wanting to use it / shape it / be in it more. I wrote this whole blog post, which (however self-indulgent and meandering it may be) is the longest-form writing I’ve managed to do in ages. I even went to a local market today and bought a mirror, which probably doesn’t sound like much, but it’s literally the first time I ever have. I’ve always recoiled from mirrors. But now, somehow, even before any visible changes whatsoever have occurred, I find I just don’t hate the idea of seeing myself anymore.

Now, I obviously have no way of separating out to what degree any of these are actually chemical versus simply the excitement of embarking on a big and long-awaited change. It’s probably always a mixture, and ultimately the exact ratio isn’t terribly important. But one perceptible effect that I’m confident is chemical (cut to the Cyproterone looking guilty) is the way that my sex drive has vanished without a trace. That’ll probably sound ominous to a lot of people, but I’ve honestly experienced it as a pretty pure and profound relief. It’s led to me feeling much friendlier towards my genitals: like they’re gentler and chiller and more a real part of me. (Contra’s bit about the feminine penis was, I’m realising, a little bit life-changing for me. It was the first time I can recall somebody articulating a physical effect of hormones that I was capable of realising that I wanted.)

This will all keep shifting, of course. In relation to the sex drive, I’ve heard a number of trans women describe the process of sexual rebuilding on estrogen as like: your old sex drive gets absolutely nuked from orbit – no survivors – but then, slowly, something new starts growing, not quite ‘in place’ of the old thing, but in a slightly different place, which can make it tricky to even recognise it as a sex drive, because it feels so different from the only reference-point for that you’ve ever had. That’s not been every trans woman on HRT’s experience – every part of this is variable – but I genuinely hope it’s mine. I’m really curious to know what might start growing in the places inside me I don’t know about yet.

There’s one last little story I want to relate. A few days ago, I was sitting on my couch reading and listening to Carlo Giustini, when I glanced up from the book and looked over at the Lucy Dacus poster on my wall. I suddenly remembered this essay she wrote about coming out, and all the little ways we usually don’t get to have it happen on our terms, and I remembered the line “Coming out can feel like giving in”, and before I knew it, I was crying.

I’ve always been a decent crier; this isn’t some stoic facade that’s never been pierced. (My facade is and has always been a pincushion.) But something about how close to the surface those tears were did feel meaningfully new to me. Historically, my crying has required a slower build than that: a steady uphill walk up to the emotional precipice. But this was like: five seconds ago I was reading about something completely unrelated, and now I’m crying. Which –

I’m sorry, I know this probably sounds chintzy and cornball, but … is that not more me? Is that not drawing closer to me my more inhibited and authentic feelings? Me suddenly crying because of a line from a Lucy Dacus essay about being queer is obviously not the strange bit here; that makes all the sense in the world. The strange part is that, when I first read the essay last year, I didn’t cry. I really liked the essay, and shared it with a few people, and remembered it – but I didn’t cry. And like, clearly that’s where you’ve got a problem, right? That’s where you’ve got a body clogged with alien chemicals gumming up the works, rusting the pipes, and getting in the way of the business at hand, which is being a weepy lesbian.

(ಥ﹏ಥ)

Look: there’s a lot more here that I don’t know than that I do, and almost all of what’s going to happen is still to come. It feels ludicrous to say given how long this post has turned out to be, but there honestly are a ton of aspects of this that I haven’t even touched on. (Visiting a sperm bank! Wild new HRT virility research that means I may not have needed to visit the sperm bank! The complex semiosis of facial hair! Questions of differential outness! My name!) But in the interests of having this be readable by anybody at all – if you’re still here, I love you – I’m going to wrap it up here.

So far, I feel really good about the decision to start HRT. It’s making me feel more like myself, and making ‘myself’ feel like a better thing to be. It feels surreal and satisfying and obviously where I want to be going, and I don’t know what more I could ask from a tiny quarter-pill and a little goop on my thigh.